Malaysia’s history of hedging wasn’t always evident. Initially, the nation was established under the auspices of, and defended by, Western powers. The formation of Malaysia in 1963, which was brokered by the British, led to a conflict with Indonesia. Jakarta viewed the new nation as being a British puppet state.

Faced with this onslaught, Malaysia owed its precarious existence to the might of the Western powers. Malaysia survived, backed by the UK and aided by the US, which held an antagonistic view towards then Indonesian president Sukarno.

But Malaysia’s foreign policy would soon undergo a profound transformation. Facing the American non-committal attitude under the Nixon Doctrine in 1969 and Britain’s decision to retreat from east of Suez, Malaysia’s leaders realised the country would need to defend its own interests in a changing global order.

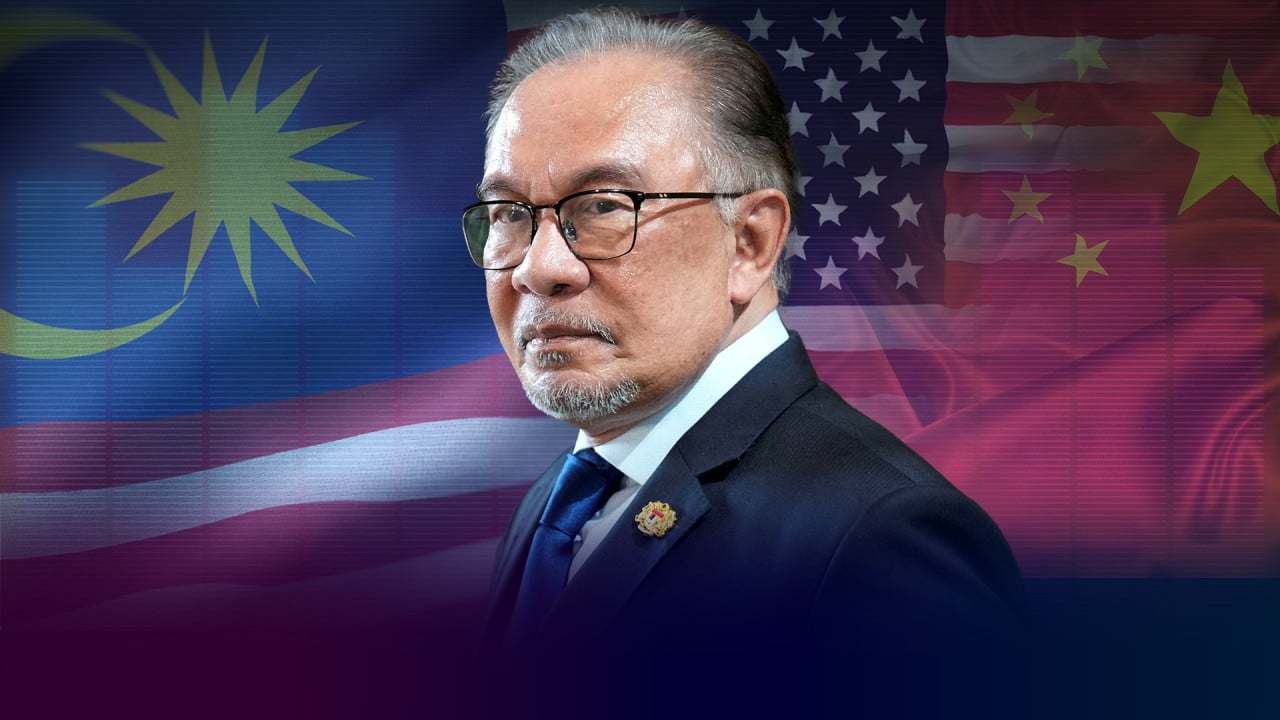

Originally published in 1996, Anwar’s view of the world in The Asian Renaissance envisioned an Asian alternative to the European model, emphasising a departure from the imitation of Western models of development and modernisation.

Anwar argues that Asia must chart its own path without severing its ties with the past. Asian civilisations risk deterioration if they follow the same trajectory as the West, which often entails a loss of cultural identity. The Western-dominated global order needs restructuring to birth a truly pluralistic modus vivendi, a prescient message forecasting a multipolar future.

However one views these developments, Anwar’s world view seems to be a prophetic and expedient tool for understanding Malaysia’s diplomacy. The Asian Renaissance is finally here.

Malaysia’s alignment with Brics is a logical extension of its long-standing policy of hedging. This strategy allows Malaysia to seize economic opportunities, enhance its geopolitical influence and help shape a multipolar global order. Overanalysing this move risks misunderstanding Malaysia’s intentions. There might be a new director, but it is still La Bohème that’s playing.

Syed Nizamuddin Bin Sayed Khassim is an administrative and diplomatic officer with the Malaysian government. This article reflects his personal views and is not a statement of the Malaysian government’s position